Mustang Panda - When Operationalising IoCs Don't Go To Plan

Overview

Recently I’ve been looking to improve my threat actor infrastructure tracking capabilities, and dust off my IOC pivoting skills—given I’ve spent considerable time lately building infrastructure as code and exploring AI capabilities rather than pure threat analysis full time. To that end, I found a great writeup by Kaspersky where they explored one of the latest campaigns conducted by Mustang Panda, a Chinese state-sponsored threat actor group known for conducting cyber-espionage operations. In this latest campaign, the group updated its CoolClient backdoor to a version that can steal login data from browsers, monitor the clipboard, and gather details about a compromised endpoint.

The question is, if Kaspersky wrote such a great blog post, why am I writing one? Well, while I don’t intend to copy the works of Kaspersky, I do intend to explore what other informaton can be gleaned from the campaign. To that end, this blog will cover:

- Taking the indicators of compromise Kaspersky provided

- Conducting IoC pivoting to identify other infrastructure assoicated with Mustang Panda

- Provide threat information that can be operationalised through MITRE ATT&CK coverage, diamond modelling, and threat hunting considerations

Spoiler alert, this investigation places more of a focus on the methodology I took to identify infrastructure, with an emphasis that you won’t always be successful in finding a ton of things - but given this is a nation-state actor, we expect their capability will be a cut above the rest. In later blogs, both as my skills improve and my threat actor research in this blog diversifies, I’ll be able to showcase more fruitful finds. But with that said, lets crack on.

IoCs identified

The below IoCs were identified by Kaspersky during their analysis of the latest campaign, linked here, I had no part in producing these, but we will use them to attempt to find other infrastructure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

+++ CoolClient C2s +++

account.hamsterxnxx[.]com

popnike-share[.]com

japan.Lenovoappstore[.]com

+++ Samples CoolClient +++

F518D8E5FE70D9090F6280C68A95998F libngs.dll

1A61564841BBBB8E7774CBBEB3C68D5D loader.dat

AEB25C9A286EE4C25CA55B72A42EFA2C main.dat

6B7300A8B3F4AAC40EEECFD7BC47EE7C time.dat

+++ Browser Login Data Stealer +++

1A5A9C013CE1B65ABC75D809A25D36A7 Variant A

E1B7EF0F3AC0A0A64F86E220F362B149 Variant B

DA6F89F15094FD3F74BA186954BE6B05 Variant C

+++ Scripts +++

C19BD9E6F649DF1DF385DEEF94E0E8C4 1.bat

838B591722512368F81298C313E37412 Ttraazcs32.ps1

A4D7147F0B1CA737BFC133349841AABA t.ps1

+++ FTP server +++

113.23.212[.]15

Hunting Adversary Infrastructure

Now that we have the IoCs, we can begin to map them to real infrastructure. Infrastructure hunting is a blend of art and science, in so much that it requires hypothesis generation, and for you to experiment and test for the most useful outcomes.

FTP

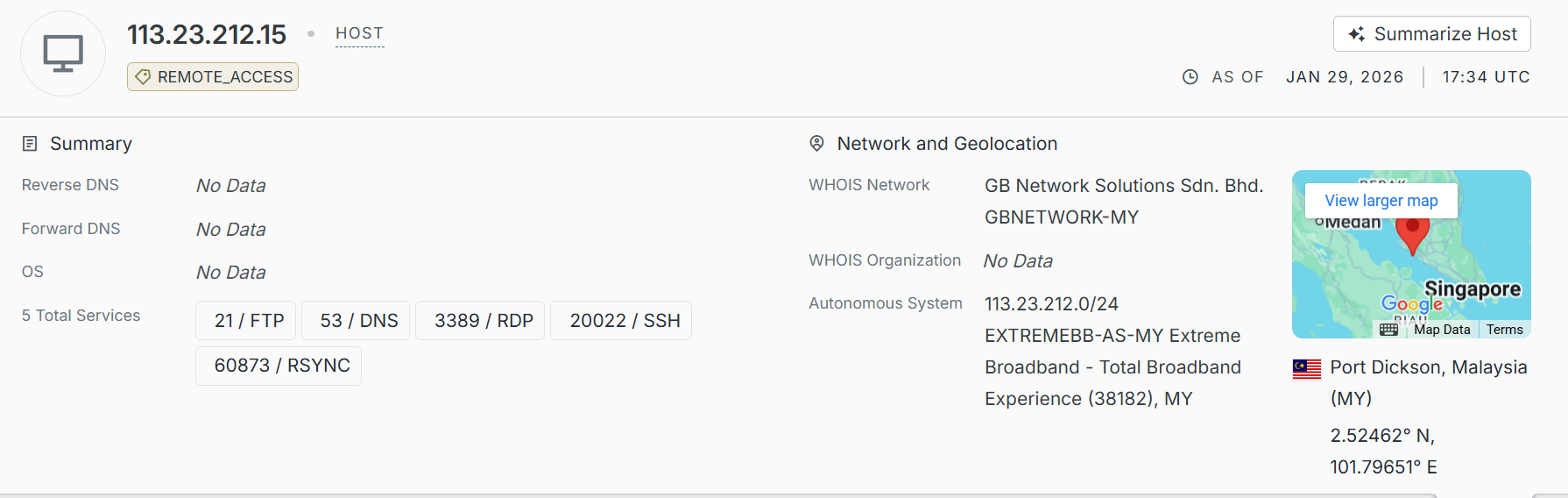

In any case, I started with the FTP server identified (113.23.212[.]15) in the last section. Using Cencys, I ran a search for the IP and identified it.

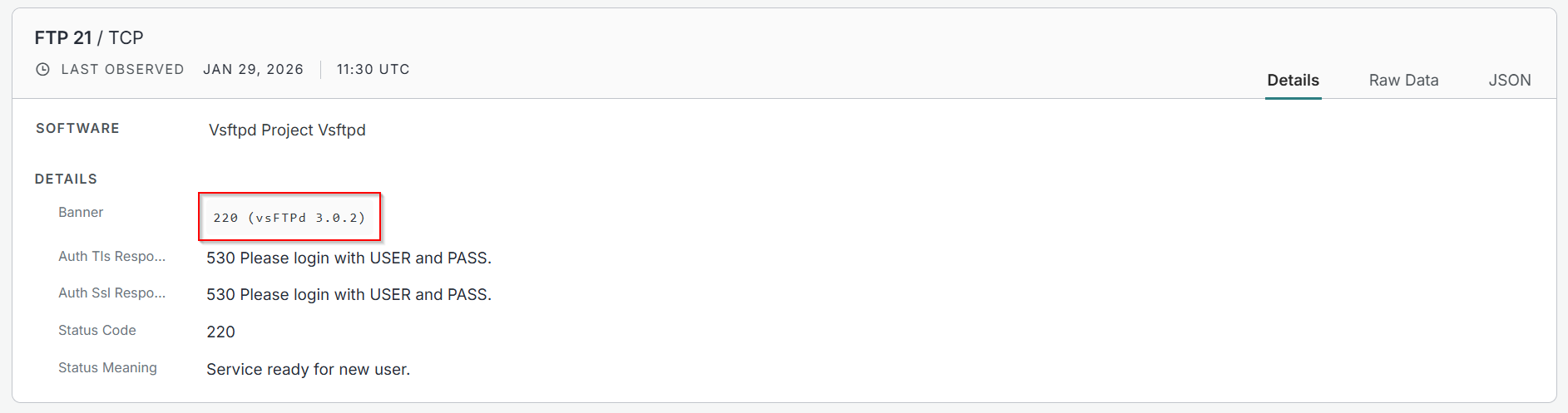

It has a number of services associated with it, including SSH and FTP. After checking FTP, I found the banner, something we could run a search on.

This search on its own produced thousands of results. Sure, some of the results would be Mustang Panda infrastructure, but there are also thousands of false positives; this isn’t great for us.

Progressing from here, I combined the banner search with the automomous system name (ASN) acting upon the hypothesis that threat actors deploy their infrastructure on the same ASN, which in this case is EXTREMEBB-AS-MY Extreme Broadband - Total Broadband Experience. The search query is below:

1

host.services.banner = "220 (vsFTPd 3.0.2)\r\n" and host.autonomous_system.name="EXTREMEBB-AS-MY Extreme Broadband - Total Broadband Experience"

This yielded only six results, including the confirmed IP address from the Kaspersky IoCs. The next step is to check these five IP addresses in VirusTotal to see if any of them flag up.

All of the IPs were clean on Virustotal, meaning I had to change my focus area. I checked for related IP addresses, domains, and detections - for all intents and purposes these IPs were clean; onto SSH then.

SSH

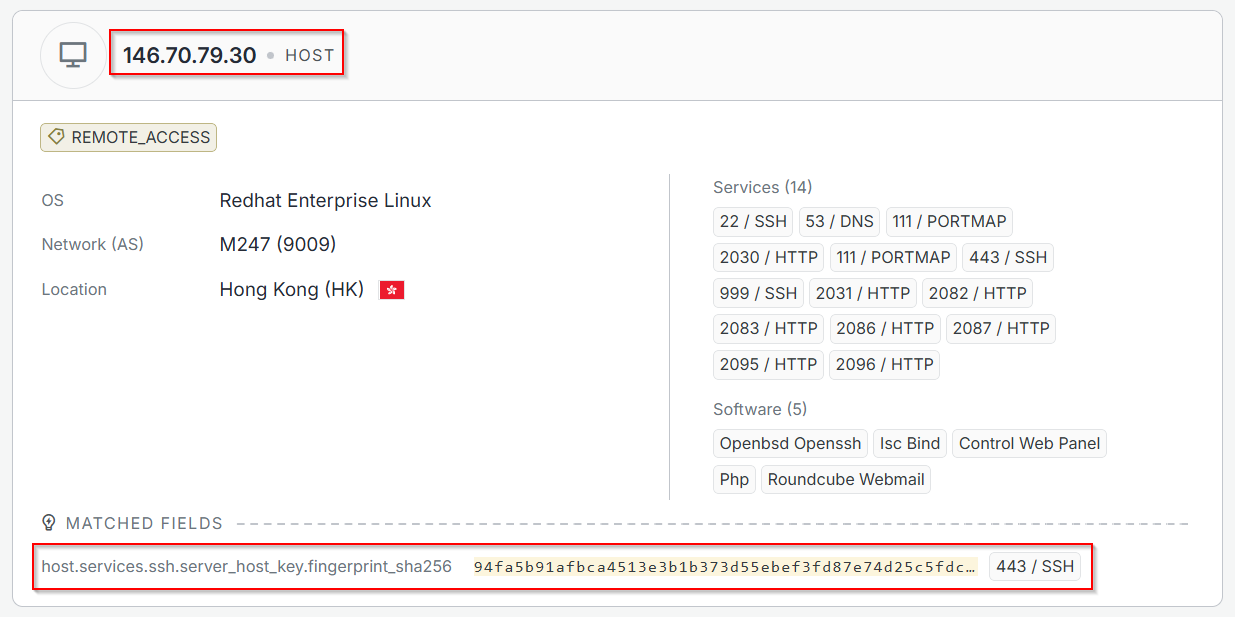

With FTP not yielding any fruit, I went over to SSH, and things were a little more fruitful.

1

host.services.ssh.server_host_key.fingerprint_sha256 = "94fa5b91afbca4513e3b1b373d55ebef3fd87e74d25c5fdc271dc7bca08c777b"

The fingerprint is unique to each SSH server much of the time, and having this key allows us to assess whether the threat actor has deployed further infrastructure using the same key; so I tested this hypothesis. Usually, every SSH server deployment has a new public/private key pair, but if the operator manually copies their key across servers (for easier infrastructure administration) then we can use that information to fingprint other infrastructure, which I did. Running a search on the fingerpirnt above provided another IP address (146.70.79[.]30).

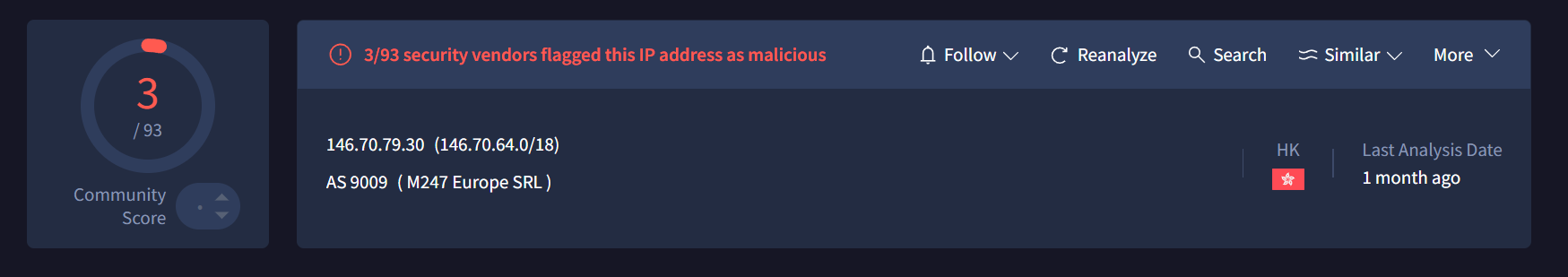

This host appears to be a Roundcube server, Rondcude being a webmail software. I checked the domain on VirusTotal, and is seemingly worth investigating further.

After going through VirusTotal, checking relations and seeing if any other behavioral indicators are shown, I ended up hot out of luck.

Presenting What We’ve Found

It seems like I don’t have a great deal to present, but CTI isn’t always about describing whats there, it’s also about describing whats not there - which I admit sounds cryptic and like I am smoking copium.

So, what does the data from this campaign actually tell us? What I see is that Mustang Panda:

- The group is very careful not share the same infrastructure for different operations

- There was very limited sharing of SSH keys between machines, showing they’re not lazy operators

- The group has used minimal viable infrastructure, the bare minumum to get the job done

Thanks for reading this blog, I know it wasn’t massively extensive, and was more about me dusting off a skill set I’ve not used in a long time, but I thought I’d have a go and writing the blog same day, given how recent the intrusions were. In following blogs as I develop my skills, I fully expect these research pieces to be a lot more extensive and successful.